This is the second article in a series that explores twenty-years of Sobey Art Award data. This post considers what the data can tell us about the gender and racial diversity of contemporary artists in Canada.

The Sobey Art Award marked its twentieth anniversary in 2022 by nominating a record number of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People Of Colour) artists. Just over half (13) of the 25 artists on the longlist for 2022 are what Statistics Canada categorizes as visible minorities or, in more recent terminology, a "racialized group" within Canada's larger white population. Another six artists on the 2022 longlist identify as Indigenous or Métis bringing the total number of BIPOC artists to 19. The final shortlist of five artists again emphasised this BIPOC presence by naming Krystle Silverfox (Indigenous), Divya Mehra (Indian descent), Stanley Février (Haitian), Azza El Siddique (Sudanese), and Tyshan Wright (Afro-Jamaican descent) as the runners-up for the $100,000 prize. Winnipeg artist, Divya Mehra was named the winner in the Fall of 2022.

The selection was, in many ways, not surprising. By 2020, museums and other cultural institutions around the world, including the National Gallery of Canada which administers the Sobey Art Award, were undergoing a major cultural rupture. Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, and the BIPOC movements were demanding that cultural institutions evaluate their representation of minority groups and seriously consider their long exclusion of BIPOC artists and cultural workers. All of this has led to a push for greater diversity and equitable representation of BIPOC artists in contemporary art in Canada and elsewhere.

After twenty years, the Sobey nomination lists provide a good source for understanding this shift and evaluating the gender and racial diversity of Canada's contemporary artists.1 At first glance, the longlists present a picture of a fairly equitable representation of gender. When the full list of 475 nominated artists and collectives is taken into account, there are 237 males, 224 females, and 14 artists or collectives who identify as gender neutral.2 When duplicate nominations are removed and the 331 individual artists are considered there is an equal number of male and female artists (160 each) as well as 11 gender neutral artists.

Gender equality, however, has not always been the case. In the first ten years of the award (2002-2012), 137 male artists or collectives were nominated versus 83 female artists or collectives (and five gender neutral artists) (here I include repeat nominations).3 In the ten years following (2013-2022), these figures are nearly reversed with 100 male nominations versus 141 female nominations (nine gender neutral). The difference has resulted in the current balance when the twenty-year period is taken into account.

When only the shortlists and winners are considered gender equality is not sustained even over the twenty-year period. Of the 90 artists or collectives shortlisted (again I include repeat nominations but exclude the year 2020 which did not have a shortlist or a single winner), 49 (54%) are male and 39 (43%) female. Two gender neutral artists made the shortlists. Of the 18 winners, 10 are male (56%) and 8 (44%) female. These figures indicate that there has been some gains for female artists over the twenty years, but also show that male artists have received greater recognition as winners of this prestigious award.

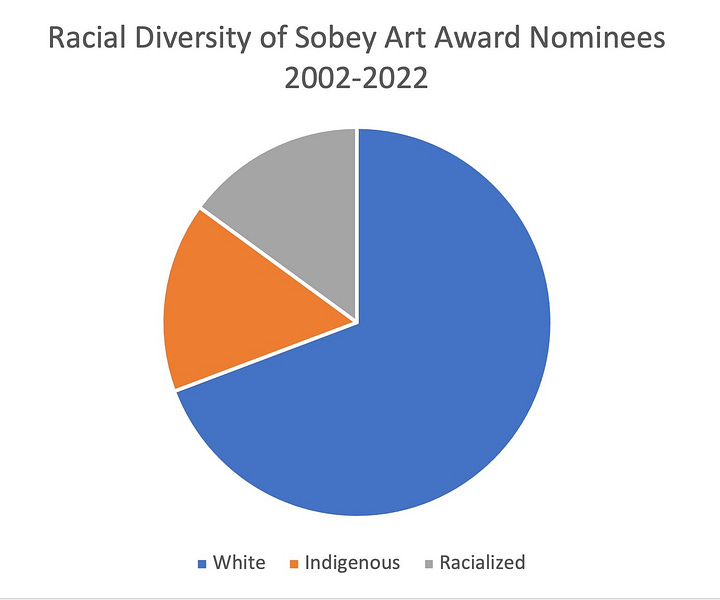

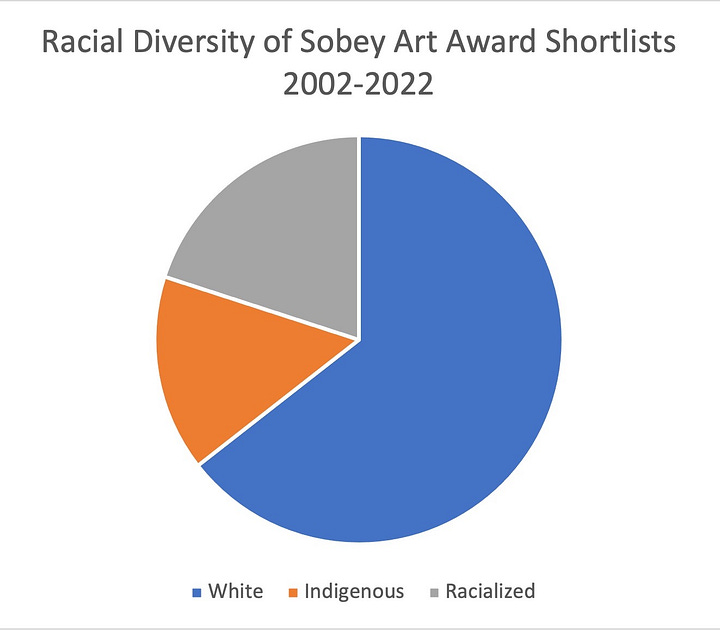

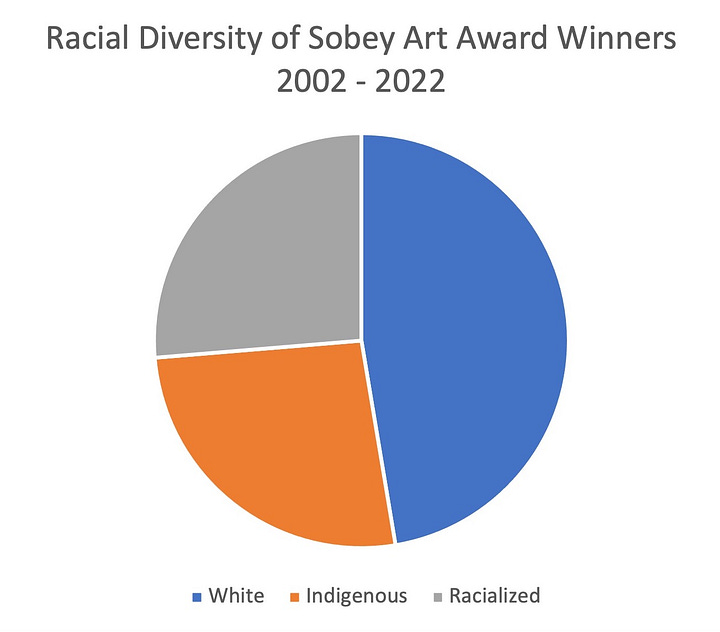

Canada’s Indigenous and Métis artists fare better in the nominations. Of the 475 nominated artists over the twenty-year period, 75 identify as Indigenous or Métis. This represents 16% of the nominated artists overall. Fourteen of these Indigenous or Métis artists made the shortlists (16%) and six took the top prize over the twenty-year period: Brian Jungen (2002), Annie Pootoogook (2006), Duane Linklater (2013), Nadia Myre (2014), Ursula Johnson (2017), and Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory (2021). This means that a full 33% of the award winners over the twenty year period are Indigenous or Métis. This is an impressive number considering that the Indigenous population in Canada according to Statistics Canada, as of 2021, is approximately 5%.

Once again, like the results on gender, the data shows a shift between the first and second ten-year periods. From 2002 to 2012, 17 Indigenous or Métis artists were nominated (8%) out of 225 and only two were shortlisted (4%), Brian Jungen and Annie Pootoogook. Both, however, won the prize that year which represented 22% of the winners across the first ten years of the award. The nominations increased in the next ten years with 45 Indigenous or Métis artists on the longlist (18%), 12 on the shortlist (27%), and four winners (44%). All of these figures, except the shortlist in the first ten years, are well above the national average indicating that Indigenous and Métis artists have been well-recognized throughout the twenty-year history of the Sobey Art Award.

Other BIPOC artists in Canada do not fare as well as Indigenous and Métis artists. According to Statistics Canada, 26.5% of Canada’s population belongs to a racialized group. Over the twenty-year period, 71 artists who identify as Asian, Filipino, Middle Eastern, Indian, or of African descent have been nominated for a Sobey Art Award (duplicates included). This represents just 15% of nominations, far below the national average for racialized people in Canada.

Again, as with the gender nominations, there is a marked shift in the data between the decades. The first ten years of the award saw an even lower representation of BIPOC artists with just 19 artists nominated (8%), six shortlisted (13%), and only one winner, Tim Lee (2008) (11%). Over the next ten years, the longlist numbers rose with 52 nominations (21%) from 2013 to 2022. Then, as if to make up for the shortfall, the shortlists and winners lists include an over-representation of racialized artists. Twelve artists made the shortlists (27%) and four of these were winners (44%): Abbas Akhavan (2015), Kapwani Kiwanga (2018), Stephanie Comilang (2019), and Divya Mehra (2022).

What does this tell us about diversity in Canadian contemporary art? This analysis indicates that there is a fairly equal number of female and male contemporary artists practicing in Canada. Male artists, however, are still more likely to gain recognition than female artists. The nominee lists also indicate that there are a representative number of Indigenous and Métis artists being recognized as contemporary artists in Canada. Their success on the shortlists and winners lists suggest that Indigenous and Métis artists have a very favourable prospect for gaining recognition.

Racialized people in Canada, on the other hand, are not represented according to their actual numbers in the Canadian population. The nominations of racialized artists did not begin to increase until 2017 when nominations rose to 12%. In 2020, the percentage grew to 24% and then, in 2022, the nominations more than doubled, reaching 52% and well above the national average of 26.5%. Only in the past two years, then, have racialized artists gained significant recognition as Canadian contemporary artists.

This data also highlights that an artist’s identity is of significant value for both the Sobey Art Award and, by extension, Canadian contemporary art. The sudden shifts in recognition of female and BIPOC artists over the years, suggests that gender and racial identity matter and are taken into account by the award juries even if an artist's identity (other than age and citizenship status) is not cited as a criterion for an award nomination. This is especially evident in the rapid increase of BIPOC nominations and winners in the last few years of the award. Their favourable recognition, acknowledges that there are some extraordinary BIPOC artists practicing in Canada, but also suggests that, in keeping with popular social movements, an artist's identity has emerged as one of the deciding factors that "makes" Canadian art contemporary.

See my previous post, "Sobey Art Award and Canadian Contemporary Art."

Several collectives are duos comprising a male and a female artist. To keep the count equal to the number of nominations, I alternated the gender designations for these duos by counting the first duo as female, the second as male, the third as female, and so on. When there were more than two artists in a collective and a mix of genders I assigned the gender of the majority – i.e. a trio of two males and a female was assigned male. Citing gender neutrality as an identity is a recent phenomenon and I may have missed a number of artists who have changed their identity since their nomination. I provide a count of these artists but there is too little data to provide any sort of meaningful analysis.

The only academic study that I could find that uses Sobey Art Award data also notes the disparity between male and female artists in the first nine years of the award. See Joyce Zemans and Amy C. Wallace, "Where are the Women? Updating the Account!" RACAR: Revue d'art canadienne/ Canadian Art Review 38, 1 (November 1, 2013): DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1066661ar.

That was a great deep dive into the numbers Marie. Although I don't know for sure if what you found means your last statement is correct. It would be fun to discuss that point. ie: do we need to add that point in our list of criteria for what is contemporary art? I am not sure, myself. Maybe because it seems that point is not really about the art?