Cut Piece by Yoko Ono

First version for single performer:

· Performer sits on stage with a pair of scissors in front of him.

· It is announced that members of the audience may come on stage—one at a time—to cut a small piece of the performer’s clothing to take with them.

· Performer remains motionless throughout the piece.

· Piece ends at the performer’s option.

Second version for audience:

· It is announced that members of the audience may cut each other’s clothing.

· The audience may cut as long as they wish.1

Yoko Ono first performed Cut Piece, her most famous work, in 1964 in Kyoto, Japan and then followed up with performances in New York and London. In this performance, Ono sat on the floor of an empty stage with nothing but a pair of large scissors. Audience members were invited to step up on the stage and use the scissors to cut pieces from her clothing. Throughout the performance, Ono did not move or speak, only submitted calmly to being slowly unclothed by the audience.

Over the years, Cut Piece has been heralded as a revolutionary statement on the objectification of women, a meditation on Buddhist selflessness, and as an important precursor to participatory art (art where the audience takes part). Critics have attributed many meanings to the work, yet, as Kevin Concannon’s research reveals, Ono herself never provided a consistent interpretation of Cut Piece. Instead, she referred to the work as an “event score.”2 Like a musical composition, the piece was meant to be performed again and again, at any location, and by anyone of any gender. After its initial run in the 1960s, Ono later reprised the performance herself and other artists, male and female, have performed and adapted it. Each time, the nuances of meaning were different. Thus, Concannon concludes that

readings of Cut Piece as feminist, pacifist, anti-authoritarian, Buddhist, Christian and even as a striptease—are all valid. The many and varied interpretations of Cut Piece by artist, performers, audiences, and critics testify to the work’s great power—a power embedded in its score. But most importantly, Cut Piece is an incredibly rich and poetic work that poses seldom-asked questions about the nature of art itself and in the process opens itself up to a multitude of readings.3

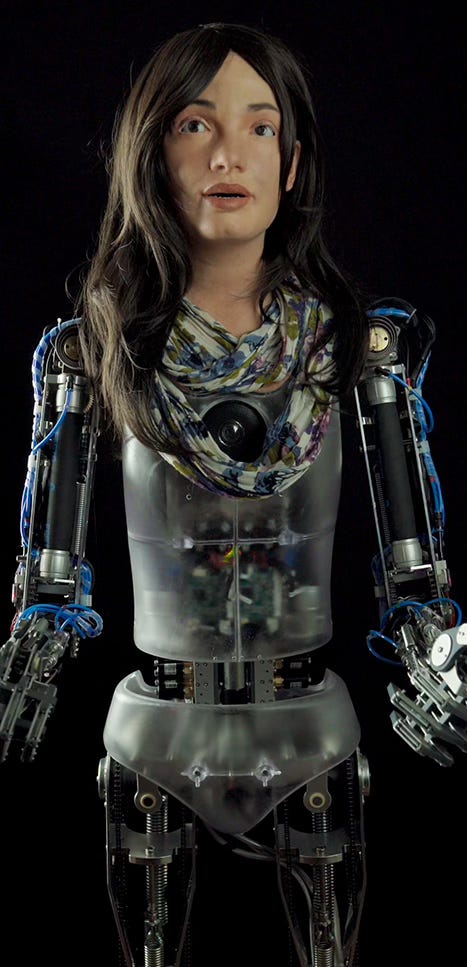

In 2019, the artist-robot, Ai-Da and her handlers (Aidan Meller and Lucy Seal) riffed off of Ono’s Cut Piece and presented a performance entitled, Privacy-A Homage to Yoko Ono, at St. Hugh’s College, University of Oxford.4 In this work, Ai-Da is unclothed and standing on a stage. This is not as revealing as it sounds. With no clothes, Ai-Da’s mechanical workings are visible through the clear molded plastic of her torso, and her arms and legs are constructed of hinged lengths of metal and wire. Like the dolls we played with as kids, she is not endowed with any semblance of sexual organs. Her feet are fixed to a stand and a power cord disappears across the stage behind her. A pile of fabric cut from recycled clothes — remnants from around the world — lay at her feet. As in Ono’s performance, audience members were invited to take part, this time to clothe Ai-Da. One at a time, a member of the audience steps up on the stage and drapes or ties a piece of fabric to Ai-Da’s body until she is fully clothed.

Throughout the performance Ai-Da does not move except for her head and eyes. As someone approaches, Ai-Da tilts her head towards them and her eyes blink. She watches the person and tries to make eye contact but does not speak. People approaching her look hesitant and shy. Not only are they stepping up on a stage in front of an audience, they are observed by a humanoid robot who acknowledges their presence with these very human cues. Some people respond with nervous giggles while others offer a polite greeting, just as they would if the figure was actually human. It is difficult, however, to distinguish whether their reactions are caused by the robot’s observation or their own discomfort with “playing” along in front of a live audience.

Ai-Da’s performance, according to her handlers,

challenges the traditional format of performance artwork, reconfiguring the relationship between human and humanoid - and raising many questions and tensions as she does so.5

These assertions, however, are not very convincing. There is little evidence that Ai-Da’s performance challenges anything or raises questions and tensions.

The significance of Ono’s Cut Piece is derived, primarily, from the fact that Ono is a living, breathing woman. Unclothing her is weighted with all the human values around gender and sexuality, values that differ in each cultural environment and period in time that the work is performed. The richness of meaning cannot be replicated with a mechanical device that is merely shaped in the semblance of a woman.

Ono’s performance is also significant because she turned the tables on what a performance artwork could be. In a performance the artist uses her own body and her body becomes, for the duration of the performance, the art object. By inviting the audience to participate, she makes them part of the artwork for the duration of their presence on the stage. At the end of the performance, the artist becomes herself and the art object disappears; all that is left of the artwork is the viewer’s experience; the memory and meaning of what they saw.

Ai-Da, on the other hand, has no autonomous agency. She must be set up on stage, programmed to do certain actions, and powered by outside sources that have to be activated. When the performance is over, she cannot leave the stage. She remains there as an object, albeit one that has some kinetic capabilities. In the end, the real performance is not enacted by Ai-Da but by the audience as they drape and dress the animated sculpture on the stage.

You can compare the two performances in the videos below.

The Lonely Palette Podcast provides an excellent discussion on, and historical overview of, Cut Piece.

Please feel free to share your thoughts on whether these two works are “cut from the same cloth.”

As quoted in Kevin Concannon, “Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece : From Text to Performance and Back Again,” PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art, 90 (Volume 30, Number 3) (September 2008): 82.

Concannon, “Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece,” 82.

Concannon, “Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece,” 92.

100% agree with you! I hate the AI pretendian disguise. More and more attempts to co-opt humanity in all it's naturally human joy and misery. Game playing until eventually it won't be.