“I am a contemporary artist and I am contemporary art” — Ai-Da, TEDTalk, Oxford, 2020

Ai-Da Robot was born in 2019 and has been working on her contemporary art career for only four years. She has already had several solo exhibitions, participated in group shows, given public lectures on her work, and sold drawings, paintings, and sculptures to avid collectors. Then, on November 7, her painting, A.I. God: Portrait of Alan Turing, sold at Sotheby’s art auction in London for over a million dollars. The sale, according to Art Newspaper, set “a new record for a work of art created by a robot.” Pretty darn good for a young, emerging artist!

But, seriously, can an AI robot become a contemporary artist; that is an artist who has the potential to gain solo exhibitions at the MoMA or the Tate Modern and climb up the ranking charts to the top 100?

If we consider the criteria and art-world activities that bring objects and artists into view (a subject I have often covered here on Making & Meaning) there is no apparent reason why an AI robot should not become a famous contemporary artist.

Most artists, as my research of the Sobey Art Award has shown, begin their journey as contemporary artists by enrolling in a higher education program such as a Bachelor or Masters of Fine Arts degree. These programs, as Gary Alan Fine notes in his study of MFA programs, allow an aspiring artist to fine-tune their artistic practice and develop relationships with art-world peers who can eventually support their emergence as contemporary artists.1 Still, as my research has also shown, there are some artists who bypass this formal training and enter the contemporary art world through a combination of mentorships and serendipity. This would be the case for Ai-Da Robot. She (as her creators prefer to call her) was created by Aidan Meller, a former British gallerist, in partnership with scientists at Oxford University and the robotics company, Engineered Arts Inc. The creator’s objective was to produce a humanoid robot that would be capable of making art. AI specialists provided Ai-Da with an education – that is, the data and algorithms that allow her to make artistic decisions and speak about art making – and the mechanical ability to make physical art objects. These creators, or what might now be called managers, are curating her entry into the contemporary art world.

To become a contemporary artist, however, one must first produce an object or activity that can be recognized as contemporary art. With the help of some human intervention, Ai-Da is physically able to draw, paint, and employ digital and photographic media to come up with original images, sculptures, and designs. Since her debut in 2019, Ai-Da has produced painted portraits of herself and others, made abstract paintings, designed sculptures and functional ware, enacted a performance, and made the painted portrait that sold at Sotheby’s. In speaking engagements, Ai-Da has also demonstrated that she has mastered an appropriate art discourse where she eloquently articulates the meaning and significance of her work in the context of contemporary life.

Producing an original object, however, is not enough for any would-be artist. The object must be accepted and recognized as art by agents and institutions in the Art World. The premier demonstration of this recognition is when the objects are exhibited to the public in reputable commercial or public galleries. It is these exhibitions, which are usually accompanied by justifying texts, that confirm the status of an object as art. The exhibition is where the object becomes art and, by extension, the maker becomes an artist.

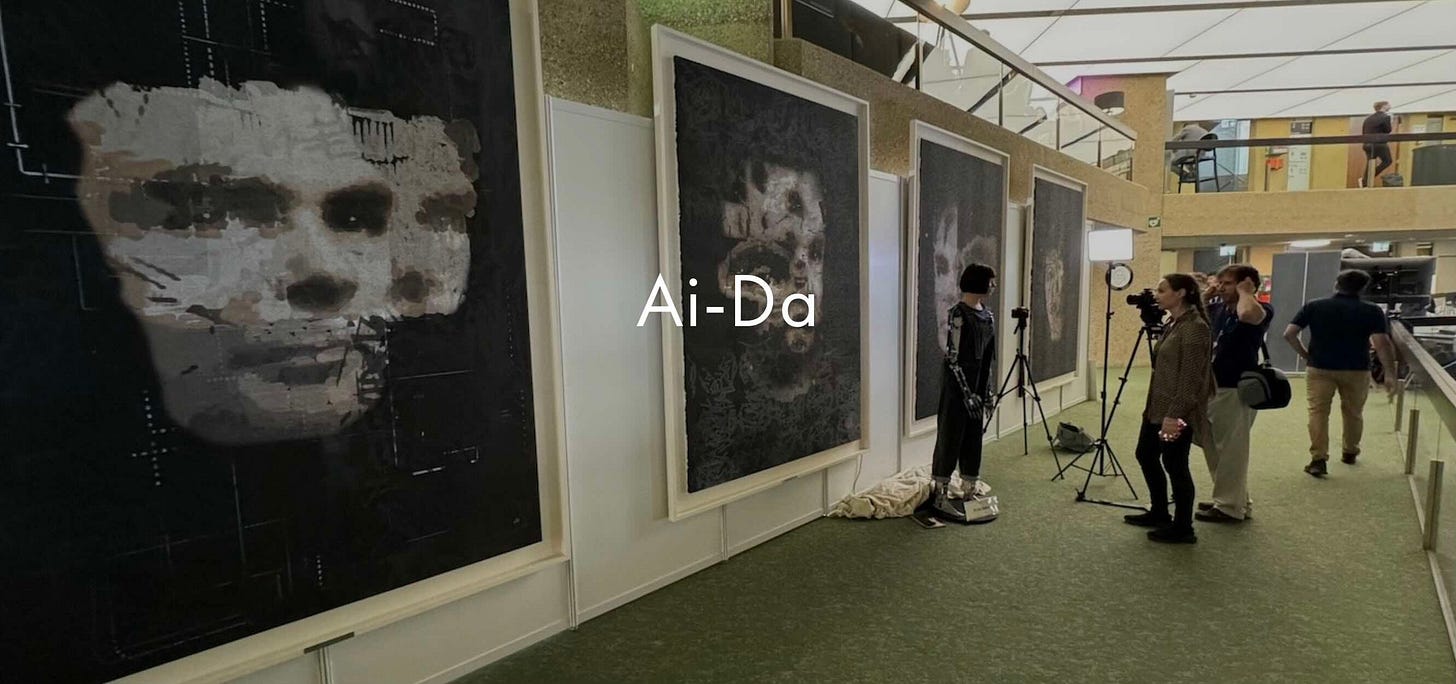

For such a young artist, Ai-Da has already accumulated an impressive record of exhibitions. Her exhibitions are even registered on the art database, ArtFacts.net. On ArtFacts, Ai-Da is described as an “ultra-contemporary” artist2 who has had four documented solo exhibitions and three group exhibitions. The database ranks her in the top 100,000 artists in the world and in the top 10,000 in Britian; a very respectable rank for a young, emerging contemporary artist.

ArtFacts has recorded two commercial galleries that have shown Ai-Da’s work: König Galerie and Annka Kultys Gallery. König Galerie is a major German gallery with exhibition spaces in Berlin, Munich, Mexico City, and Seoul. They represent significant contemporary artists like Alicja Kwade, Jeremy Shaw, Erwin Wurm, and Phyllida Barlow. Ai-Da’s work was included in a group exhibition organized by the gallery, The Artist is Online: Painting and Sculpture in the Post Digital Age, in 2021.

Annka Kultys Gallery is a London gallery specializing in contemporary artists who explore the use of digital and AI technology in their practices. The gallery is newer and not as well-known as the König Galerie but does represent a few significant artists such as Thomas Hirschhorn, Cao Fei, and Danh Vo. The gallery also bills itself as the first gallery to represent a robot artist, Ai-Da. Like the other artists they represent, Ai-Da is given her own webpage with images of her work and a list of her exhibitions and press coverage. Her exhibitions include four solo shows at Annka Kultys Gallery, the König exhibition in 2021, exhibitions at The Design Museum, Tate Exchange, and Barbican Gallery in London in 2019, an exhibition at Ars Electronica in Dubai and Abu Dhabi, and another at the University of Oxford.

With all of these exhibitions in reputable galleries and museums, Ai-Da would appear to have successfully passed through the initial stages of developing an artistic career and should be called a contemporary artist. Yet, despite these achievements and enthusiastic reception from the popular media, Ai-Da has not been as eagerly feted in the art press. Her detractors have questioned the originality and quality of her work, the true authorship of this work, and whether a non-sentient machine can actually be considered “an artist” capable of expressing original thoughts about contemporary life.

For example, Imogen West-Knight writing about Ai-Da’s 2021 exhibition at the Design Museum, Ai-Da: Portrait of the Robot, in ArtReview, claims

the artist is what is on show here, because the art itself is fine, but would be of no interest had it not been created by a creepy talking robot. The most eye-catching works in a selection of not very eye-catching works are three large oil self-portraits in pastel blues, lavenders and pinks. They’re the sort of thing you might expect to see on the cover of an EDM best-of compilation.

West-Knight also points out that

the process by which these pieces were created is a little convoluted. Ai-Da did not ‘paint’ them, per se. She made preparatory sketches that were then fleshed out by being fed back into her own algorithm, and then a human art technician, Suzie Emery, whose name you do have to hunt down to find, did the painting. Ai-Da then did some further mark-making on the paint surface to complete the work. The reason it’s so complicated is because the truth is that, so far, AI robots don’t make massively interesting art without significant human input.

Naomi Rea, in an article on Artnet, makes similar charges. In her article, “A Gallery Has Sold More Than $1 Million in Art Made by an Android, But Collectors Are Buying Into a Sexist Fantasy,” she concludes that while

a genuine artist-AI would be awesome (and terrifying), we do not yet have the scientific capabilities to imbue sentience and artistic feeling onto the pattern-making machines we are able to animate….In reality, though, this kind of art is the result of human collaborators writing code, in Ai-Da’s case researchers at Oxford and Leeds University.

All the authors also take offence at Ai-Da’s female persona which her creators have explained is modelled on, and named after, the early computing pioneer, Ada Lovelace (1815-1852). Dan Fox’s article, for Frieze Magazine is called “The Ugly Objectification Behind the World’s First Robot Artist” and he refuses to refer to Ai-Da as a she. Again, like the other authors, he questions the creative potential of an anthropomorphic machine:

Despite Meller’s claims – and no matter how many times Ai-Da is referred to in the third person, as if to will it into life – it is not innately creative. It needs electricity. It needs to be switched on and set into ‘drawing mode’ by humans. Ai-Da can’t choose or refuse its subjects, it can’t switch up styles, backtrack, discard work it considers a failure, ascribe meaning to what it makes. Ai-Da is a tool, not an artist.

Reading these reactions to Ai-Da and her work, I cannot help but think of Duchamp’s experiments with the readymade. In 1917, he anonymously presented an industrial-made urinal to an art exhibition. The work, Fountain, was rejected because it could not be recognized as art. Now, over a century later, Fountain is cited as a founding work of art that helped shape what we know as contemporary art.

Fountain, along with Duchamp’s other readymades, demonstrated that anything — an ordinary urinal, bicycle wheel, bottle rack, or chair — can become art even when it has not been made by the artist. Duchamp’s experiments also showed us that the meaning and significance of an artwork is not intrinsic to the artwork itself, but applied after its presentation by those who accept it as art. More radically, the readymades demonstrated that art does not have to be visually appealling. Rather, it is the artist’s original concept that counts, and how it and its associated object is transformed into an artwork through exhibitions and texts.3

Like Duchamp’s Fountain, the emergence of Ai-Da appears to present a conundrum that has unsettled the contemporary art world. This time it is not a question of what can be art, but rather, who or what can make art. Can a machine that has no consciousness, sensual experience of the world, or human emotions produce an original concept that the Art World can value as art? The very presence of Ai-Da has introduced this question and a challenge to the notion that only sentient humans are capable of an original creative concept.

Gary Alan Fine, Talking Art: The Culture of Practice and the Practice of Culture in MFA Education (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018).

ArtFacts and other institutions use the term “ultra-contemporary” as a period designation usually for young and emerging artists. ArtFacts includes artists born in 1975 and later in this category.

For a good history and analysis of Duchamp’s development of the readymade and curatorial experiments see Elena Filipovic, The Apparently Marginal Activities of Marcel Duchamp (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016).

Thanks for writing this Marie. I have to admit I have a hard time with this one, like some of the other critics did in your piece.

To me, Ai-da has no soul, so there is nothing real to move me at the heart of these creations. (However, I can at the same time think some of the results are amazing, and I might be curious about them if I saw them hanging on a wall and didnt know how they were created).

I think for me, the false note is ascribing this art to a robot who interacts with us and is assigned a kind of artistic personhood as opposed to a computer produced art product that we are aware of as such, but isnt trying to justify its existence and pretending to be humanoid.

Also watching the video I think Ai-da is getting farther away from the uncanny valley type of robot experience which makes it, for me even more unsettling. I'm not ready for this...let alone ready for it in contemporary art lol.

This would be a good topic to discuss at M and M. Sorry I missed last week with no notice. Things at work are a bit insane.