This post continues my examination of the Sobey Art Award data. In this post I consider how exhibitions contribute to an artist’s recognition.

To be nominated for a Sobey Art Award an artist must demonstrate “a commitment to artistic practice” and have gained “recognition by peers, critics and/or curators.”1 In the contemporary art world, an artist demonstrates these requirements by exhibiting artwork to the public. An art exhibition affirms that an artist has produced a body of work (“a commitment to artistic practice") and that an artist has “peers, critics and/or curators” who recognize the objects as art and the maker as an artist.

But, how does an artist gain entry into this world of exhibitions and recognition? As I related in the first part of this study, “Becoming a Contemporary Artist: Part I: Education,” a post-secondary visual art education, that is a Bachelor of Fine Art (BFA) or a Master of Fine Art (MFA) degree or equivalent, can help to increase an aspiring artist’s opportunities to move through the circles of recognition described by Alan Bowness.2 A BFA and, even more so, an MFA introduces and familiarizes an aspiring artist with acceptable forms of art and with the discourses that are used to validate contemporary art. The educational and social circles of the academic environment also introduces the artist to peers such as other artists, professors, and curators who can vouch for the authenticity of an artist’s work and provide future exhibition opportunities.

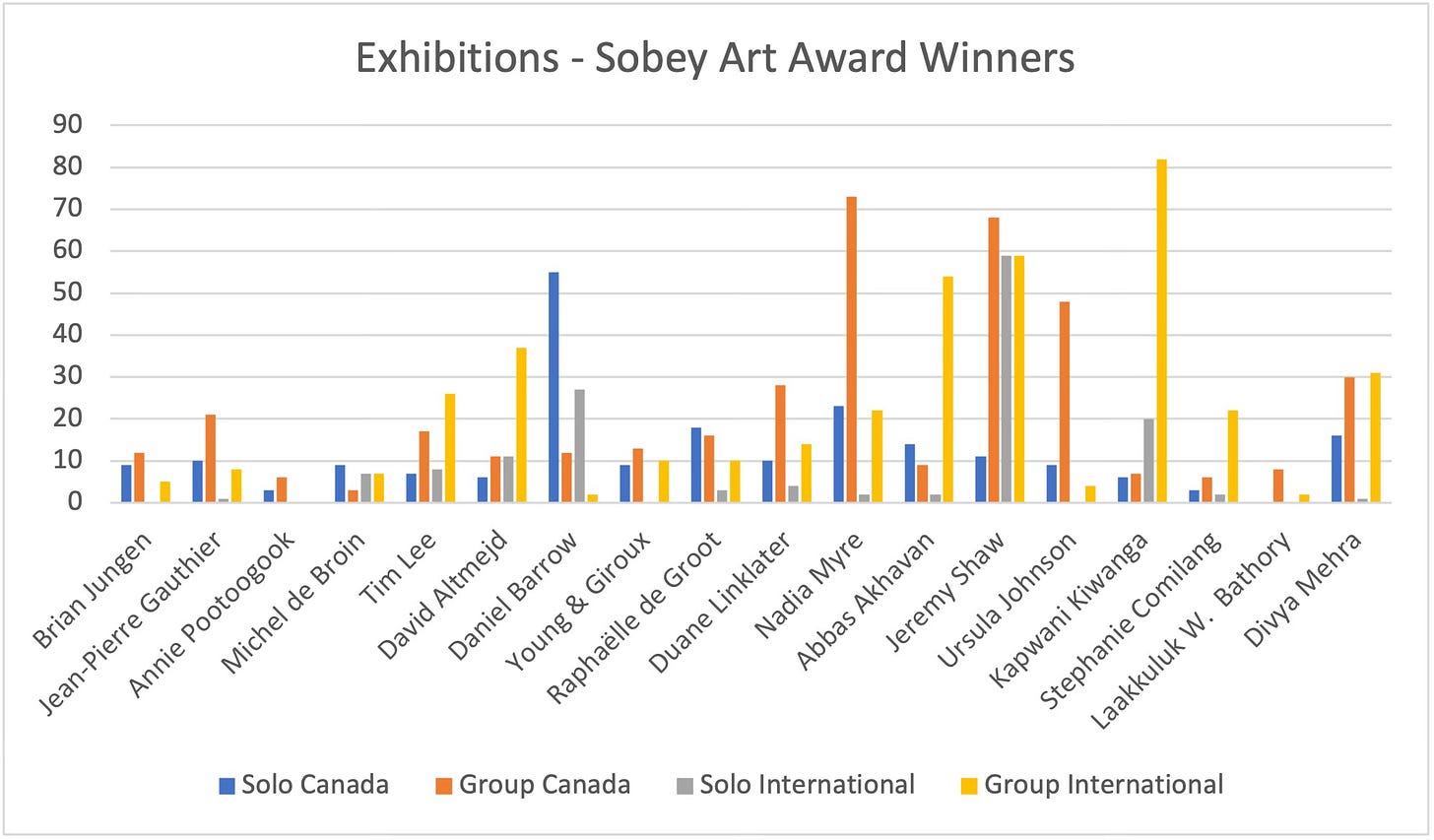

The path through the circles of recognition, however, is not the same for every artist as the data from the Sobey Art Awards indicates. To understand how exhibitions contributed to the recognition of the Sobey nominees, I narrowed my research set to the 18 winners of the award from 2012 to 2022.3 Based on publicly available individual curricula vitae, I documented each artist’s exhibitions prior to their award nomination.4 The chart indicates the varied results of this data collection and how each artist has a very different exhibition profile.

All of the winning artists, like all of the nominated Sobey artists, had one or more group or solo exhibitions in appropriate venues prior to nomination. The mix of solo, group, Canadian and international exhibitions, and the total numbers of exhibitions that each artist had, however, varies considerably. This variation is due to a number of factors such as the type of artwork an artist produces, the strength of the artist’s contacts, where the artist lives, and the number of appropriate exhibiting venues this location offers.

Most communities in Canada have one or more venues and events where art can be exhibited. In the hierarchical world of art, however, these venues are not all equal. Small galleries exhibiting crafts and other works by amateur artists, for example, are not considered suitable venues for an aspiring contemporary artist. Instead, aspiring artists soon learn, often in their post-secondary studies, which venues are appropriate and which will bring them the most recognition and prestige. In Canada these include publicly-funded community galleries that feature the work of “professional” and sometimes local amateur artists, artist-run centres which are cooperative spaces operated by artists and also publicly-funded, provincial art museums, university art galleries, commercial galleries that market contemporary art, and in some cities, museums wholly funded by a philanthropic organization. Other exhibition opportunities include art fairs, festivals, contests, and civic or provincial biennales, but again these events must be notably recognized as focusing on contemporary art.

Each of these venues and events brings an artist a different level of prestige and recognition. For example, an exhibition at a provincial museum has greater recognition value than an exhibition at a small university gallery in Nanaimo, British Columbia. Likewise, international exhibitions, group or solo, add yet another level of prestige to an artist’s oeuvre. These distinctions, while never openly mentioned in the Sobey Art Award criteria, are demonstrated in the types of exhibitions recorded on an artist’s resumé. Again, the short bio of the winner of the 2012 Sobey Art Award, Raphaëlle de Groot, published by the Sobey Art Award illustrates the type of exhibitions that the Art World tends to highlight.

Raphaëlle de Groot lives and works in Montreal and holds an MFA from the Université du Québec à Montréal. She has presented her work in Canada and Europe since the late 1990s including solo exhibitions at Dare-Dare; Centre d'histoire de Montréal; Cittadellarte-Fondazione Pistoletto, Biella, Italy; Leeds City Art Gallery UK; Galerie de l'UQAM; Le Quartier, Centre d'art contemporain de Quimper, France; Southern Alberta Art Gallery; La Chambre Glanche; and Optica. Group exhibitions include the 2008 Québec Triennial at the Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal; Femmes artistes: L'éclatement des frontières, 1965-2000 at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec; and Archi-féministes! at Optica. De Groot recently collaborated with the Musée de la civilization (Gatineau) and the Musée Colby-Curtis (Stanstead) for a project that was presented at Galerie Graff in November and December 2012.5

De Groot also provides a good example of how a contemporary artist gains recognition through education, exhibitions, and art-world relationships. At age 19, de Groot began her studies in fine art by enrolling in the BFA program at the Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM). Here she would have learned the discourse of contemporary art, met important artistic peers, and begun to develop her research and performance-based collaborative practice which, over the years, has included the use of multiple media, installations, long-term research projects with communities outside of the art gallery, social interventions, and live performances.

De Groot graduated from the BFA program in 1997 and immediately began exhibiting her work in appropriate venues such as non-profit artist-run centres or university galleries. These types of contemporary art venues often provide new art graduates with their first professional exhibitions. De Groot took part in five group exhibitions and six solo shows from 1997 through 2001.

Gaining a solo exhibition so soon after graduating, especially from a BFA program, is remarkable and de Groot’s artistic practice may have been an asset in this regard. Her 1997 solo exhibition, Reconnaissance, was hosted by Dare-Dare, an artist-run centre in Montreal dedicated to supporting “innovative practices.” Reconnaissance was an installation that explored the idea of the body and touch using film projection, a microfiche reader on a desk, and a 3D model of de Groot’s magnified skin surface that visitors could touch. This type of installation with multi-media features is difficult to incorporate in a group show, especially one in a small gallery space. Also, unlike a painter or sculptor who must build a large body of work before exhibiting, many of de Groot’s works are installations created during the exhibition, community interventions, and performances all of which can be produced and adapted quickly to a particular space.

De Groot appears to have had plenty of early support for her work in Montréal and beyond. In these first few years of her career, her work was introduced in Europe. In 2000, Dare-Dare included de Groot in a group exhibition, L’algèbre d’Ariane, that travelled to the Centre Les Brasseurs in Liège, Belgium as a part of an exchange program. In 2001, de Groot’s work was also included in a group exhibition of five artists, Point de chute, at Galerie de l’UQAM. That exhibition then travelled to Brussels, Belgium where it was shown at the Centre d’art contemporain de Bruxelles. In 2002, de Groot took up a two-year residency at the Accademia UNIDEE in Biella, Italy which is supported by the well-known Italian artist, Michelangelo Pistoletto. This opportunity appears to have resulted in de Groot’s work being included in another European exhibition, Michelangelo Pistoletto & Cittadellarte &, at the Musée d’art contemporain in Antwerp, Belgium. More European exhibitions, group and solo, followed in Spain, France, and England.

In 2004, De Groot returned to art studies at UQAM and completed a Maîtrise en arts visuels et médiatiques (Masters of visual and media arts) in 2007. In his study of MFA programs, Gary Fine found that it is not uncommon for artists who are already established with exhibitions to enroll in an MFA program.6 The MFA often solidifies their practice, adds to their Art World contacts, and in most countries also qualifies the artist to take up a teaching position in a post-secondary institution. In Canada, most artists are unable to survive without another form of paying employment. After graduating, de Groot held teaching positions at the University of Lethbridge, UQAM, and Concordia University in Montréal.

Throughout her exhibiting career, one advocate stands out as especially significant, Louise Déry. In 1997, the same year de Groot graduated with her BFA at UQAM, Déry assumed the role of director at Galerie de l’UQAM, the university’s campus art gallery. She curated the exhibition, Point de chute, that included de Groot’s work in 2001 and in 2006, Déry gave de Groot a solo exhibition, En exercice, which was also accompanied by a catalogue and essay written by Déry. Some years later, the exhibition was reprised in Venice, En exercice à Venise in 2013. In 2009, Déry was invited to sit on the Sobey Art Award jury and was on the jury again in 2012, the very year de Groot won the award.7

The Sobey Art Award, like an exhibition, also adds to de Groot’s recognition as a contemporary artist not only in Montreal but in Canada and internationally. De Groot was nominated for the award five times. She was first nominated in 2002, the first year of the award, and then again in 2007. In 2008, her nomination resulted in a move to the shortlist. She was again nominated in 2009 and finally made the winner’s list in 2012.

De Groot’s transition through the circles of recognition appears fairly consistent and follows a similar pattern to other Sobey winners. Strong variations, however, still arise because of the type of work an artist produces, where an artist lives, and how easily an artist is able to make important contacts in the artistic centres of Canada. Artists who studied or live outside of Canada, for example, tend to have more international exhibitions (Kapwani Kiwanga, David Altmejd, Jeremy Shaw) or artists who live in small, isolated communities far from artistic centres tend to have far fewer exhibitions (Annie Pootoogook, Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory). Artists who work in performance or video may have more solo exhibits because of how the work is presented (Daniel Barrow), or artists who address certain current themes like colonialization and Indigenous identity may have more group exhibitions (Nadia Myre, Ursula Johnson). Ultimately, what this data indicates is that the Sobey Art Award is not given out solely on basis of an artist’s exhibition record. Rather, exhibitions are significant for bringing an artist into the Art World and into the orbit of those who choose the winners of the Sobey Art Award.

https://www.gallery.ca/for-professionals/media/press-releases/call-for-nominations-for-the-2023-sobey-art-award

Alan Bowness, The Conditions of Success: How the Modern Artist Rises to Fame (London: Thames and Hudson, 1989).

The Sobey Art Award was initiated in 2002 as a biennial award. That changed in 2006 when it was given each year following. In 2020, no shortlist or single winners were chosen because of the COVID pandemic. Instead the prize money was awarded equally to all 25 nominatees. For this reason, I have excluded 2020 from shortlist and winner data.

These artists’ resumés may not accurately reflect all of the artist’s exhibitions as some resumés list only “selected” exhibitions.

Ray Cronin, Sara Fillmore, and Donna Wellard, Sobey Art Award/Prix artistique Sobey: 10th Anniversary/10e anniversaire (Halifax: Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, 2013), 91.

Gary Alan Fine, Talking Art: The Culture of Practice and the Practice of Culture in MFA Education (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018).

Cronin et al, Sobey Art Award, 86.

That last sentence is a kicker!