This post continues my examination of the Sobey Art Award data. In this, and a future post, I look at what the data can tell us about becoming a contemporary artist.

Raphaëlle de Groot lives and works in Montreal and holds an MFA from the Université du Québec à Montréal. She has presented her work in Canada and Europe since the late 1990s including solo exhibitions at Dare-Dare; Centre d'histoire de Montréal; Cittadellarte-Fondazione Pistoletto, Biella, Italy; Leeds City Art Gallery UK; Galerie de l'UQAM; Le Quartier, Centre d'art contemporain de Quimper, France; Southern Alberta Art Gallery; La Chambre Glanche; and Optica. Group exhibitions include the 2008 Québec Triennial at the Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal; Femmes artistes: L'éclatement des frontières, 1965-2000 at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec; and Archi-féministes! at Optica. De Groot recently collaborated with the Musée de la civilization (Gatineau) and the Musée Colby-Curtis (Stanstead) for a project that was presented at Galerie Graff in November and December 2012.1

There are only three criteria for a Sobey Art Award nomination. First, an artist must be a Canadian citizen or landed immigrant; second, the artist must demonstrate “a commitment to artistic practice;” and finally, the artist must have gained “recognition by peers, critics and/or curators.”2 The nomination guidelines do not specify how the latter two criteria should be met but the short resume of the 2012 Sobey Art Award winner, Raphaëlle de Groot, suggests that education and exhibitions are at least two factors that are considered when affirming a nominee’s qualifications for the award and their status as a contemporary artist.

Unlike engineers, doctors, accountants, plumbers, electricians, lawyers, and so on, artists do not have qualifying examinations or a governing organization that confers professional status. Even a university degree in visual art, such as a Bachelor of Fine Art or a Master of Fine Art, is no guarantee that a person will be acknowledged as a professional artist. An art education, however, can enhance an artist’s opportunities to prove their “commitment to artistic practice” and gain recognition in the contemporary art world.

In his lecture, The Conditions of Success: How the Modern Artist Rises to Fame (1989), art historian and former director of the Tate Museum, Alan Bowness explained that an aspiring artist goes through “four circles of recognition” to earn a place in the Art World.3 First, an artist must have suitable peers who recognize their production as art. Second, commercial gallerist and collectors take note, exhibiting and selling the artist’s objects as art. Third, curators and museums begin to exhibit the work and justify its artification in texts.4 Finally, the work, as well as the artist, are documented into art history and accepted by the public. An arts education can assist aspiring artists in this process, especially with entering the first circle of recognition. A BFA degree usually provides some training in applied skills but also introduces artists to the theory and discourse of contemporary art and potential peers. The MFA is even more significant as it provides the final polish, so to speak, that leads the artist into the second circle of recognition and future exhibitions.

A Master of Fine Art is usually a two-year degree where each student is assigned a studio space, takes some graduate level courses in a variety of subjects, writes a thesis paper, and produces a body of work that is usually presented in a final group or solo exhibition. But the program is much more than this. As sociologists Howard Singerman and Gary Alan Fine point out, MFA programs do not teach artistic skills but situate aspiring artists into the social and ideological orbit of the contemporary art world. Studying for an MFA introduces the artist to appropriate peers and mentors, people already versed in the language and expectations of the contemporary art world. The professors in these programs are themselves graduates of MFA programs and are usually expected to be practicing contemporary artists who have extensive exhibition records. As “master” artists with experience in the Art World, these professors also have at hand a valuable network of social contacts. They can offer the MFA student an invitation into their network of curators, gallerists, and other “master” artists all of whom have the power to provide the “recognition” one needs to enter the first circle of the Art World and become a contemporary artist.

MFA programs, as Fine proposes, also have a very powerful influence on the definition of contemporary art, not from a defined curriculum but through the process of socialization that comes from group critiques and the shared ideological culture of the art program.5 During their two years of study, students are expected to present their work to their professors and academic cohort for critical discussion. It is here, that a student learns what sort of art is acceptable and what meets the expectations of contemporary art. Furthermore, through the process of critique, the student learns to verbally defend their artistic decisions and/or abandon their choices when their peers and/or faculty deem them inappropriate. The group then, through discussion and encouragement, shape a definition of what is acceptable as contemporary art. While these discussions are not guided by explicit rules there are boundaries that the student soon learns exclude certain media, methods, and subjects from the definition of contemporary art. Through this process, MFA students also develop a common language and ability to discuss their work in relation to art historical precedents and other contemporary artists. In other words, they begin to weave their own story, as artists and producers, into a common discourse about art. As Fine notes, the MFA

has come to be seen as a marker of the ability to articulate one’s intentions, to link one’s work with that of others in the field’s cartography, and to make a case that the work has a meaning, and not merely a presence.6

Finally, an MFA contributes to shaping a student’s identity as a contemporary artist. Over their two years of study, the student learns to verbally (and in written texts) justify their artistic choices and defend these practices, a skill that is important for convincing gallerists, public funding organizations, curators, and the public that what they are making is art.

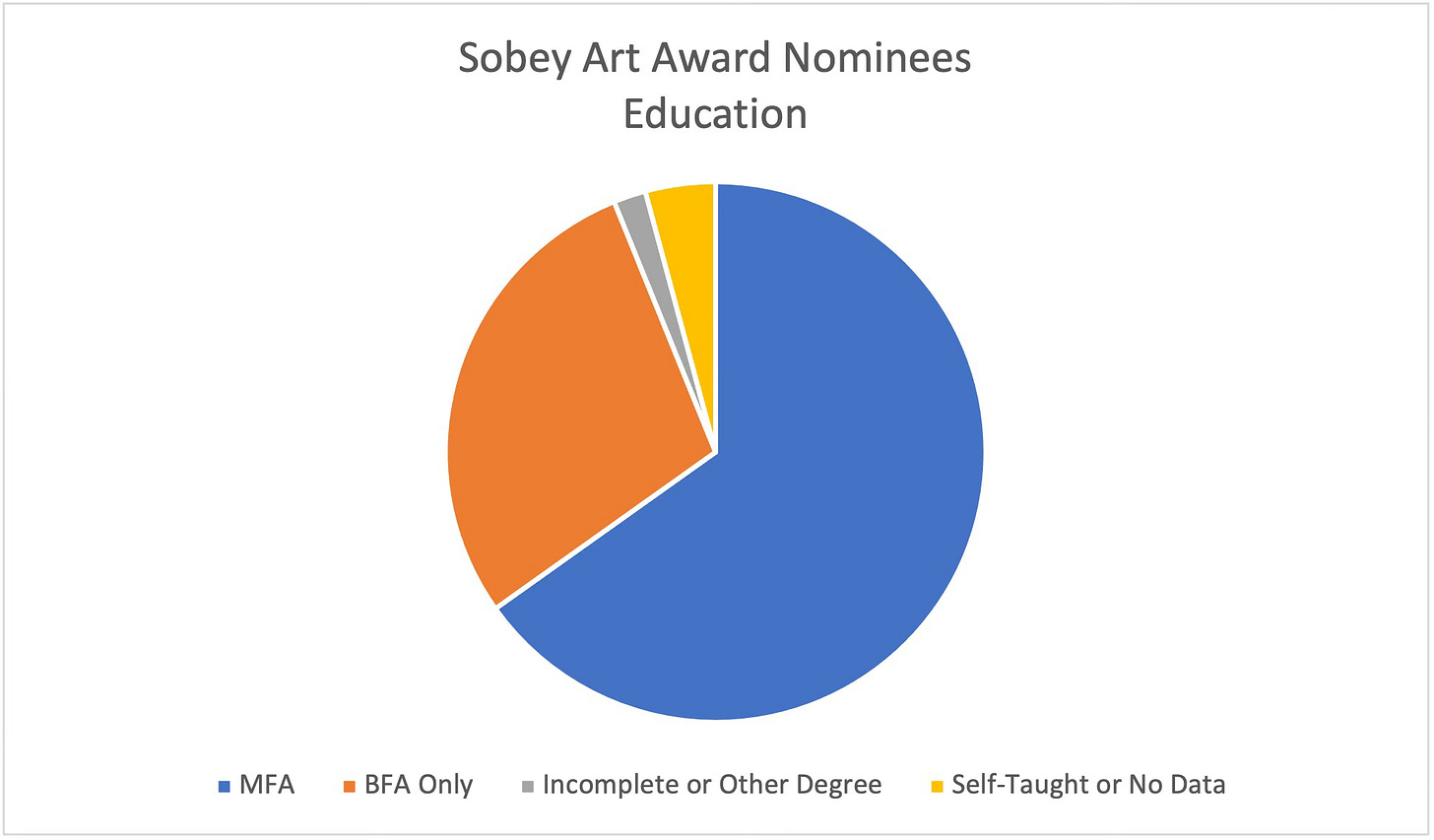

The important influence of a post-secondary art education in an artist’s entry into the four circles of recognition is clearly evident in the Sobey Art Award nominee list. At the time of their nomination, 94% of the 310 artists7 had completed a post-secondary art degree, either a BFA or an MFA, and 65 % of the total number of artists had completed an MFA. The remaining artists had post-secondary degrees in other disciplines or incomplete art studies (six), or had no post-secondary training at all (13).8 The high number of artists who have completed a degree suggests that while a formal education is not stated as a requirement for the Sobey Art Award, the acquisition of a BFA or an MFA is clearly an asset to aspiring contemporary artists.

Considering the social influence that an advanced art degree can offer an aspiring artist, I was curious to see if some art programs in Canada are favoured over others. As Fine found in his research, the top programs in the United States, such as UCLA, Columbia, and Yale are very competitive. All MFA programs in the US and Canada are modelled on the Bauhaus and structured similarly, however, each may offer some differences such as specialized studios for certain forms of artmaking (printmaking, ceramics, etc), have more prestigious faculty, or be located in major cities that have strong ties to artistic institutions and commercial galleries. Students make their choices but the more competitive institutions can choose their students.

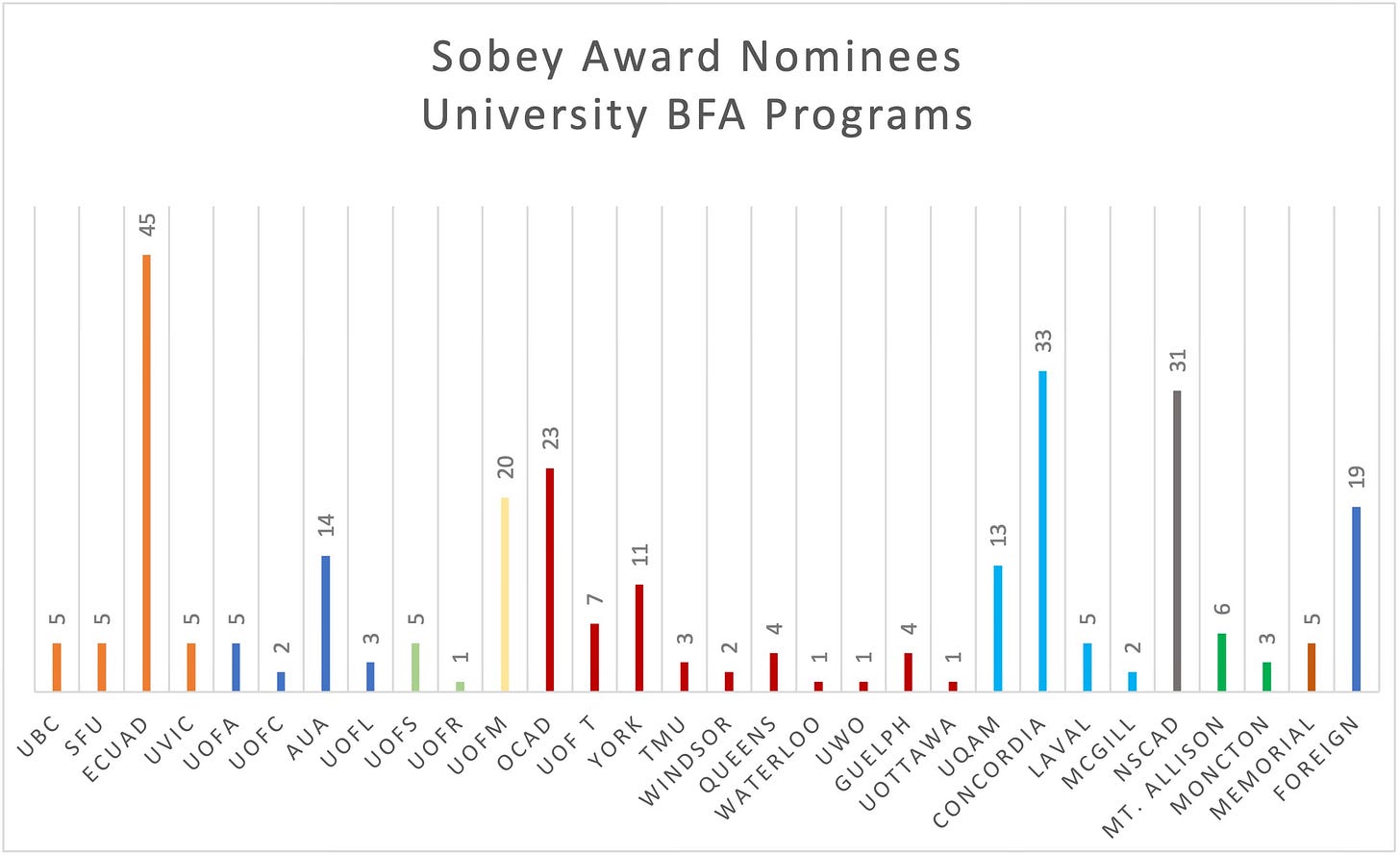

In Canada, there are four dedicated visual art institutions and numerous degree granting art programs in universities across the country. As the chart indicates, Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver, Concordia University art program in Montreal, and the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design University stand out as the most well-attended BFA art programs by Sobey nominees in Canada. These results indicate that attending certain schools may offer an advantage to aspiring artists. A more in-depth study would be needed to determine whether this is because the graduating students are better versed in making contemporary art or whether the school provides better peer support and access to the artistic community outside the institution. It should be noted here that nominators for the Sobey Art Award must be art professionals which includes professors teaching in these very institutions. Again, further research into who nominated the artists would indicate how influential Canada’s art education institutions are in introducing aspiring artists into the first two circles of recognition.

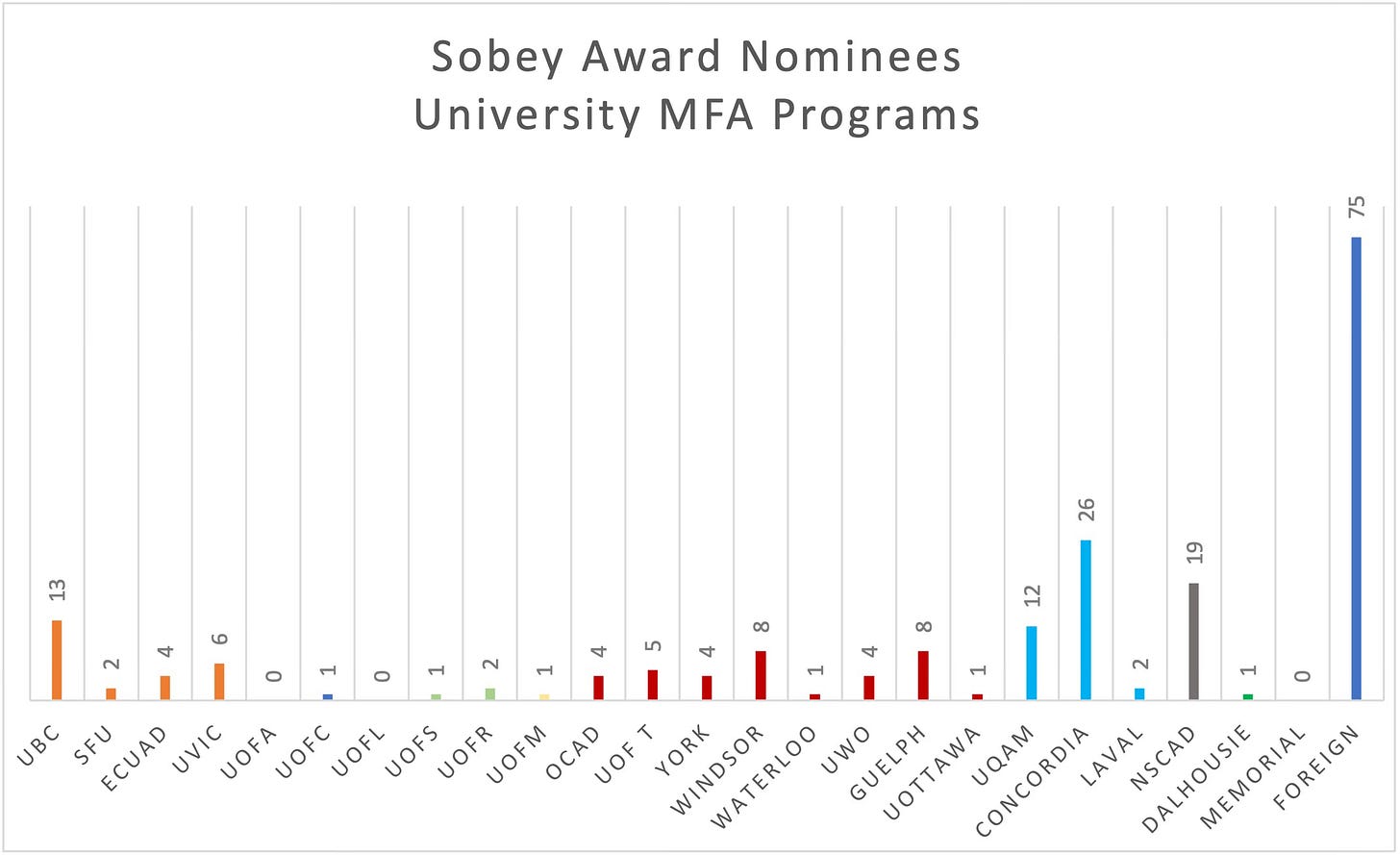

The data for MFA acquisition is quite different. This time Concordia University leads as the favoured institution, followed by NSCAD and the University of British Columbia.9 The numbers of students acquiring their MFA outside the country, however, far surpasses any of the Canadian programs suggesting that a degree outside the country is of greater value for aspiring Canadian artists. Most of these artists studied in the United States with the highest number attending Yale University, Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts at Bard College, and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Outside of North America, Goldsmiths at the University of London was the most popular choice. Each of these institutions, with their respected reputations and locations in the centres of international contemporary art, would provide Canadian artists better access to peers who could more readily elevate their recognition beyond Canada.

A foreign degree, however, does not necessarily translate into a definite win with a Canadian art award. Of the 18 winners, just over half (11) of the artists had an MFA at the time of their win and four of these had MFAs from foreign universities. Considering the high number of artists attending foreign universities (37%) this is not a surprising number. Of the other winners, five had a BFA and the remaining two artists, Annie Pootoogook (2006) and Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory (2021) had no formal training. Overall, these results suggest that a post-secondary art degree in not an absolute requirement but is a strong asset for artists as they begin their careers and seek recognition for their work and status as contemporary artists.

But what of artists, like Pootoogook and Bathory, who did not attend a post-secondary art program? Thirteen out of the 310 nominees on the Sobey list did not have any formal art training while six artists had completed some studies or had completed a degree in a different discipline. Gaining recognition in these circumstances would be much more of a challenge especially for artists living in remote areas of the country, like Pootoogook and Bathory. Annie Pootoogook (Sobey Art Award Winner 2006), for example, came from the northern territory of Nunavut in the Arctic where there is no post-secondary art program, art museums, or important contemporary art professionals.10 Instead she had to rely on others to bring her work to the attention of the institutions in the south. Her parents were both accomplished Inuit artists and served as her models for developing her artistic skills. The West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative then provided a bridge to the art world in the south and art dealers in Toronto marketed her work. Other untutored artists, like Dominique Petrin (2014) or Tyshan Wright (2022), living in Canada’s cities have less of a challenge as they have access to exhibitions of contemporary art and can develop their social network directly. Still, all of these artists would need to build relationships with suitable peers and find a strong advocate in the art world to vouch for their work.

Either way, whether an artist graduates from a post-secondary art program or forges an artistic practice without a formal education, an artist must first make objects that appropriate peers in the Art World will accept as contemporary art. This is the first circle of recognition for any artist. Education may aid in entering this circle but the work, in the end, will be the final proof of an artist’s contemporaneity and qualification for an art award like the Sobey.

Ray Cronin, Sara Fillmore, and Donna Wellard, Sobey Art Award/Prix artistique Sobey: 10th Anniversary/10e anniversaire (Halifax: Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, 2013), 91.

https://www.gallery.ca/for-professionals/media/press-releases/call-for-nominations-for-the-2023-sobey-art-award

Alan Bowness, The Conditions of Success: How the Modern Artist Rises to Fame (London: Thames and Hudson, 1989).

See my earlier post, “When is a Chair Art?”

MFA students will have been introduced to group critiques when they studied for their BFA. These critiques are usually more focused on specific assignments designed to teach compositional skills whereas at the Master’s level, the critiqueAt the undergraduate level the critique may be less rigorous but will

Gary Alan Fine, Talking Art: The Culture of Practice and the Practice of Culture in MFA Education (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 4.

The total number of artists recognized by the Sobey Art Awards is 331. This excludes duplicate nominations and includes the individual artists in collectives. To simplify my data collection for studying the educational background of nominees, I recorded the educational credentials of only one artist in each collective, the artist with the most art education.

This number includes artists who had no education or training data available.

Institutions that did not offer MFAs at the time were removed from the chart.

See my article at makingandmeaning.substack.com/p/kinngait-an-artistic-centre-on-the