Utter that so familiar name – “van Gogh” – and a series of motifs spring to mind: the great artist ravaged by madness, his severed ear, Arles, the Irises and Sunflowers, his brother Theo, his tragic death, the peintre maudit, the unrecognized genius, his contemporaries’ incomprehension, today’s record prices for his paintings, and so forth. Today, when such commonplaces are virtually universal, hardly anyone would dream of questioning the received image of van Gogh, of asking what it comprises or whence it comes — Nathalie Heinich, The Glory of Van Gogh: An Anthropology of Admiration1

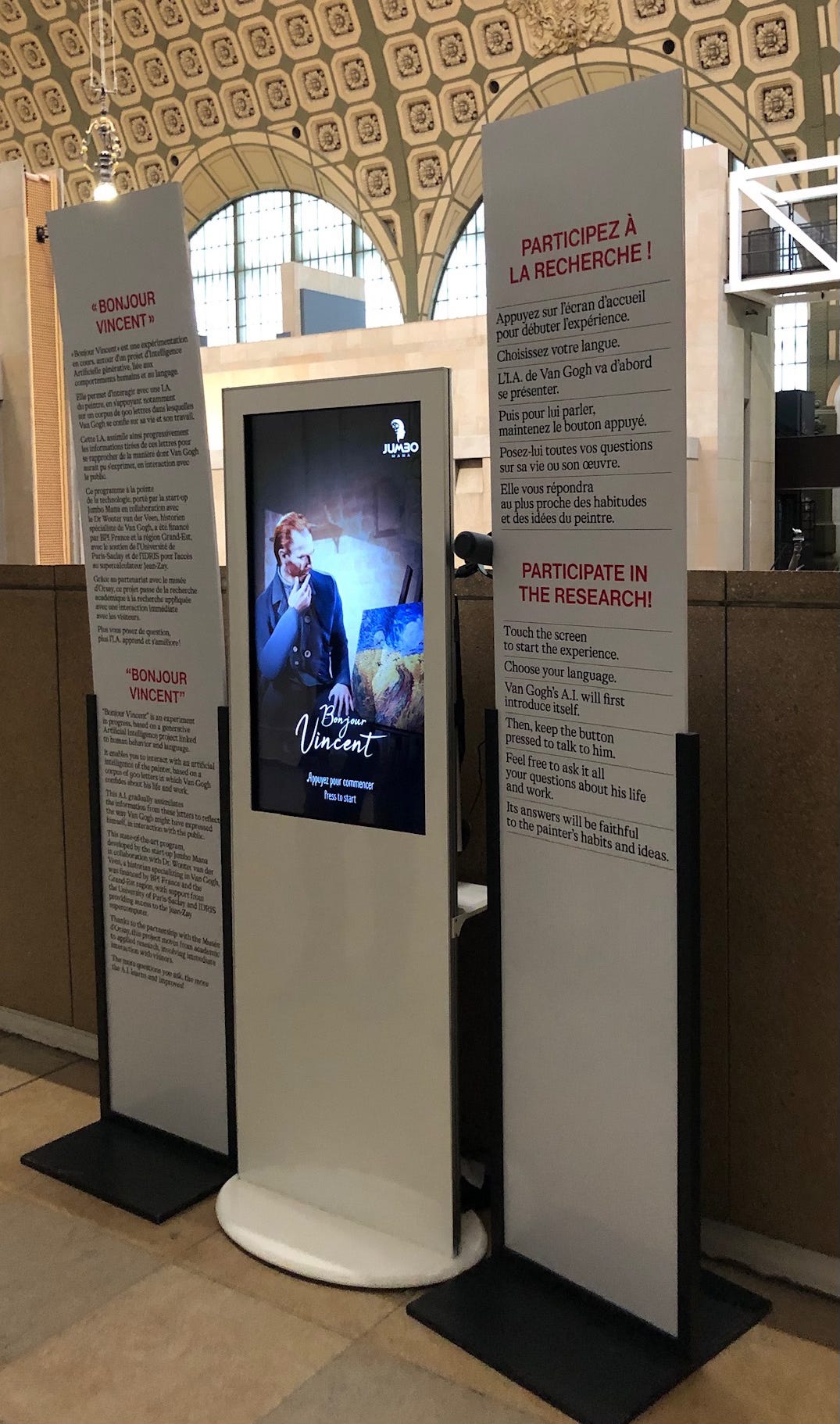

Vincent van Gogh, the simple Dutch painter who few appreciated in his lifetime, has risen again. This time he has appeared as a digital avatar in the exhibition, Van Gogh à Auvers-sur-Oise: Les derniers mois (Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise: The Final Months), at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris which just ended on February 4th. Bonjour Vincent is an animated version of van Gogh developed by the AI (Artificial Intelligence) start-up, Jumbo Mana whose tag line is “We bring characters to life.” Working with an art historian and AI researchers, Jumbo Mana loaded the avatar’s “brain” with 900 pieces of van Gogh’s personal correspondence. During the exhibit, visitors were invited to say “hello” to van Gogh and ask him questions about his art and his life. The objective of this resurrected van Gogh was to enhance the educational experience of the exhibition (think interactive didactic panel) by giving visitors the feeling that they could actually speak with the artist who produced the works on the wall. As the museum described it, Bonjour Vincent

provides a unique, personalized encounter between visitors and Vincent van Gogh. Using a microphone connected to an interactive terminal, the application enables visitors to discuss one-to-one with the artist while he’s painting his famous Wheatfield with Crows.

But the museum and the researchers also had another objective; to further refine the life-likeness of van Gogh’s AI-driven avatar in the present. As the museum explained, “The more questions you ask, the more the AI learns and improves!”

What should we make of this simulation of van Gogh? Is it just another commercial gimmick like virtual exhibitions, T-shirts, and coffee mugs that have so successfully poster-ized the life and legacy of one of the world’s most popular artists? Or, does it herald a significant shift in how we will understand art and artists into the future?

In her 1991 study, The Glory of Van Gogh: an Anthropology of Admiration, Nathalie Heinich considers how van Gogh came to be so popular. Not long after his death in 1890, artists, writers, and critics began to reconsider his artistic legacy and tied this inextricably with his tragic personal life. Prior to his death, his paintings were often met with “incomprehension” and ridicule by both the public and art-world figures such as artists, collectors, and critics. A few months before his death, one young critic, Albert Aurier, boldly wrote a favourable article about van Gogh’s work. It took several more years before others caught on to this validation. As Heinich writes,

By 1905, Dutch and French critics had cemented the main elements of his “legend”: passion, tragic fate, devotion to art, heroism, and martyrdom. Finally, three decades after his death his “critical fortune” reached its zenith on the international scene.2

The new narrative that emerged from these posthumous reassessments transformed van Gogh from an impoverished “mad” artist who no one understood to an admired hero and secular saint.

The “van Gogh effect,” as Heinich calls it, also established a new paradigm of the modern artist. The admiration for van Gogh and his work set into motion a number of changes that today seem all too common. First, the admiration for van Gogh’s illness and eccentricities introduced “the personalization of artistic greatness;”3 that is, the Art World came to value the “interiority” of the artist – the artist’s personal thoughts and feelings – as a measure of artistic value. We now consider artworks, whether they feature images of sunflowers or starry nights, to be much more than what they illustrate; they also representation the artist’s suffering, personal feelings, intellectual concerns or, more often than not today, their identities as socially neglected outsiders.

The “van Gogh effect” also gives value to “abnormality” in both an artistic and personal sense. Van Gogh’s unique painting style which was once ridiculed for its difference and his personal affectations – his “madness” and his suicide – were gradually enfolded into his mythology and transformed into signs of his singular difference as an artist. These attributes became a measure of the worthiness of his art. Carried forward in time, the value of difference and abnormality have become the “norm” even for contemporary art. We still expect art to demonstrate unique and often defiant differences (the abnormal) and value these differences as artistic achievements.4

The admiration of creative exceptionalism and originality, of course, is not unique to art or its history. We have always admired the creative genius of great inventors or artists like Michelangelo or Leonardo. As Heinich proposes,

The Vangoghian paradigm is that abnormality is no longer valued as an exception, but as the rule. The normalization of the abnormal is an a priori principle of excellence that applies to every artist. Henceforth, normality in art consists of being outside of the norms.5

Original singularity then has become an imperative that is one of the key measures of modern and contemporary art. As Renato Poggioli wrote in his treatise on the artistic avant-garde, “deviation from the norm is so regular and normal a fact that it is transformed into a canon no less exceptional than predictable.”6

A third feature of this “van Gogh effect” is that the traditional value of beauty as a measure of artistic worthiness has largely been set aside. By valorising abnormality and the “interiority” of the artist, aesthetic formal concerns about a work are secondary to these other values. As Heinich explains,

this relative dismissal of the criterion of beauty marks a change in the nature of evaluation. The latter now focuses on an earlier phase of the creative process, on the producer instead of the spectator. Henceforth, the work is to be judged less in function of the spectator’s feelings, and more in function of what the producer was “trying to say.”7

The modern artwork, as a manifestation of the artist’s intention, is presented as an “enigma,” a puzzle to be solved and writers, as we see from van Gogh’s example, quickly stepped in as the interpreters of art. Today, artist’s statements, curatorial essays, and didactic panels are an ubiquitous part of every exhibition.

Van Gogh, of course, was not the first to challenge artistic norms. Heinich’s objective in highlighting his example is that his work and his life have come to represent these significant changes in the popular imagination – in other words, van Gogh has become the avatar of modern and contemporary artists. As Heinich explains,

The new Vangoghian paradigm quite literally embodies a series of shifts in artistic value, from work to man, from normality to abnormality, from conformity to rarity, from success to incomprehension, and finally, from (spatialized) present to (temporalized) posterity. These are, in sum, the principal characteristics of the order of singularity in which the art world is henceforth ensconced. That is the essence of the great artistic revolution of modernity, the paradigm shift embodied by van Gogh.8

The contemporary art world, even with its many changes since the advent of the historical avant-garde, is still enthralled by the “van Gogh effect.” We continue to expect artworks to represent the intent, feelings, or concepts of the artist; we still expect each artist to defy the norms and create something distinctly and defiantly original; we still expect the artist to “say” something with their work, and we still admire these values over the attributes of formal beauty.

The appearance of Bonjour Vincent, this computer-generated resurrection of a long-dead artist, raises many questions about how we will come to view and value artists and art from the past, in the present, and in the future. How will this nascent intelligence evolve as it interacts with researchers and the public? And, will it eventually de-mystify the singular originality of the artistic heroes of the past like van Gogh, Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Picasso? As Heinich’s study of van Gogh demonstrates so well, contemporary art of the present relies on the beliefs formed about art in the past. These beliefs are founded on the value of difference and rarity that comes to an end with the artist’s death. How then will AI transform this value of if artists continue to live on in the guise of life-like avatars in the future? Will this new technology instigate the formation of a new paradigm for art? While I don’t propose to have the answers, it is not too soon to begin asking what this AI-generated van Gogh comprises and whence it comes.

Nathalie Heinich, The Glory of Van Gogh: An Anthropology of Admiration, trans., Paul Leduc Browne (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, [1991] 1996), xii.

Heinich, The Glory of Van Gogh, 3.

Heinich, The Glory of Van Gogh, 143.

Heinich, The Glory of Van Gogh, 143.

Heinich, The Glory of Van Gogh, 143.

Renato Poggioli, The Theory of the Avant-garde, trans., Gerald Fitzgerald (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, [1962] 1968), 56. Using different terms, others have also noted how the artistic avant-garde valued what Heinich calls here “abnormality.” Poggioli calls this anti-conventionalism the “antagonism” of the avant-garde while sociologist, Pierre Bourdieu refers to it as “anomie.” Another theorist of the avant-garde, Peter Bürger, calls it the “provocation” of the avant-garde. In my own work, I call this characteristic “dissidence” and discuss how this value has been carried over into contemporary art. See, Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde, trans., Michael Shaw (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, [1974] 1984), 55-58; Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature, edited by Randal Johnson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 252; and Marie Leduc, Dissidence: The Rise of Chinese Contemporary Art in the West (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2018).

Heinich, The Glory of Van Gogh, 144.

Heinich, The Glory of Van Gogh, 146

Thanks Marie. I enjoyed that. My main thought about the ideas was that what they are doing with the AI Van Goth project is that this is really about the AI and not really the artist or his art at all. It is one of the many ways (as you also note) that generative AI is being trained. It is starting to edge over into culture more and more and for me, while I can appreciate AI's role as a helper...for example....in the medical and other professions, I don't like to see it here. It's the uncanny valley that bothers me I think, and the trivialization of someone's humanity and creativity. What next!