We see these paintings as nobody saw them before. If we discover why this is so we shall also discover something about ourselves and the situation in which we are living - John Berger, Ways of Seeing (Part I)

Two images from my art school days are rather oddly fixed in my brain. One is of Sir Kenneth Clark, a balding older gentleman with bad teeth, who loomed over the darkened lecture hall in the 1969 documentary series, Civilisation. Dressed in a brown tweedy suit, dress shirt, and tie and with his left hand usually tucked in his pant pocket, Clark appears in almost every scene standing before the great monuments and paintings of Europe. Like an erudite travel guide he explains in his very proper English how each object represents a civilizing moment in European history.

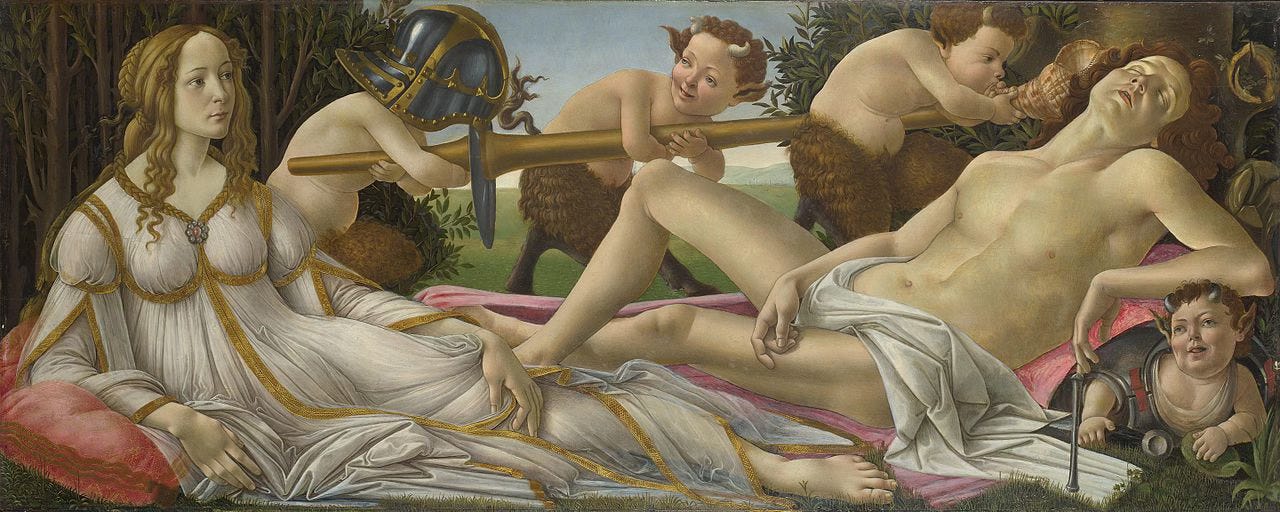

The second image is a complete contrast. In this image a young, hip John Berger, the British Marxist theorist and writer, appears in the 1972 documentary Ways of Seeing. In the first episode, he steps into the frame with his back to the camera. He has a floppy mop of long curly hair and is dressed in an open-necked patterned shirt and high-waisted pants. He approaches Botticelli’s Venus and Adonis on the wall of the National Gallery in London and, with a knife, carefully cuts into the canvas around Venus’ head. One can almost hear the shocked gasp as he removes the piece containing Venus’ head. In the rest of the series, Berger appears against a blue screen that occasionally interrupts the steady flow of images drawn from classic European masterpieces, advertising, and film. Berger’s voiceover, with its distinct lisping “r,” narrates all four episodes and explains how the great works of Western art, many of the very same masterpieces that Clark cites, have taught us how to understand the world we live in.

My recollection of these two series was piqued when I came across a work by Canadian artist, Lorna Mills. In 2015 Mills created Ways of Something, a “contemporary remake” of Berger’s documentary. In this work, Mills takes Berger’s voiceover and overlays it onto new video footage. Mills commissioned over 113 internet artists to create one minute videos in response to Berger's series. The artists gleaned images from the internet and stitched them together into short video clips that Mills then curated and arranged into four thirty-minute episodes to match Berger’s work. Mills, as far as I can tell, never appears in the series.

The three series present very different perspectives, but actually share a common thread in how each uses images to relate “the situation in which we are [or have been] living.” The images in Clark's series chronologically illustrate the foundations of a European worldview that has evolved over the centuries, and that until very recently, formed the basis of most Western art history texts. As the series unfolds over thirteen episodes, Clark celebrates each artwork as a glorious achievement that leads resolutely towards a progressive and promising future. The series takes us through museums and into the middle of historical sites that most of the students in my art college in Western Canada had never seen. On the large screen we moved with Clark among the columns of the Parthenon and through the Gothic cathedrals of France. This is perhaps why Clark’s series was so popular when it aired on BBC in England and other countries. The internet was in its infancy, televisions were small, and travel shows like Rick Steeves’ Europe were not yet common. Thus, despite Clark’s stodginess and peculiarities, the show was a hit. It expanded the “situation” we all lived in by allowing us to see art and objects from another world and to travel virtually through the most famous museums and monuments.

Clearly of another generation, Berger dressed and acted like the boys I went to high school with. His actions in the opening scene and his critical point-of-view demonstrated an irreverent challenge to the authority of my parents’ generation and to the academic world that Clark represented. While Clark steadfastly and uncritically champions the beauty and wonder of Europe’s art, Berger takes a knife to it and dissects it bit by bit. His series introduced me and my art school colleagues to look critically, to question the narratives we were told and the images that were put before us. While he never refers to his sources, Berger, like most post-modern thinkers of the time, had been coached in Marxism and the historical dialectic – for every thesis there is an antithesis. He showed us how to doubt the thesis, look for the antithesis and turn it all around into a new understanding of the images and objects around us. Over the four episodes, for example, he examines how linear perspective engages the viewer, and how photography replicates this same technique and produces a highly curated view of the world. He also points out how the objects and great monuments of Western art celebrate the value of private property and possessions, and how photography and advertising then replicate this value through the proliferation of even more images. Berger also asks the viewer to consider how women have been portrayed in the great masterpieces of art. While he does not mention it explicitly, women are virtually absent except as mothers and objects of desire in Clark's story of European art and civilization. Berger’s series then shows us how the great works of art model our social beliefs and how these values are then continually replicated in the present through a continuous production of images.

Mills’ series is something else again as it pulls us into the present. In Ways of Something, the viewer is fed a steady stream of images from video games, social media, newsfeeds, films, advertising, animated gifs, and porn sites. These images are stitched together in such a way that there is no discernible story arc. Only Berger’s voiceover guides the viewer along and Mills leaves the viewer to make her own interpretation of what his words might mean. At times the images seem to match the words, and at other times, Berger’s voice, as it is juxtaposed to new imagery, pushes us to rethink his earlier analyses in the context of the many big questions we are consumed with today: racial and gender identity, post-colonialism, mass consumerism, and environmental disaster.

Mill’s Ways of Something is rich with the panoply of images that have arrived with the invention of personal cameras and the internet. Made in 2015, however, Ways of Something is already receding into the past. Newer technical innovations and AI will soon lead the way to another way of seeing ourselves and “the situation in which we are living.”

You can view Lorna Mills’ Ways of Something on her website here. Both Civilisation and Ways of Seeing are BBC productions. They may be available at your local library or on some streaming services. Ways of Seeing was also published as a small book. The text and images from this book can be viewed on-line here.

Wonderful reflection! I enjoyed reading it very much. Clark's and Berger's projects center on one person, narrating his opinions (albeit knowledgeable ones), a male-centered perspective and projection. Mills' project is a collective endeavor, subversive, multi-media, and raising more questions than the creators can answer, which correlate to the criterions we have discussed on contemporary art :)